All articles

Comms Leaders Find Their Edge By Translating, Not Broadcasting, Complex Information

Natasha Bethea Goodwin, VP of Membership at the Information Technology Industry Council, on converting complex policy expertise into actionable narratives.

Key Points

Association communications leaders create the most value when they function as translators between internal policy experts and external member audiences, not as broadcast engines.

Natasha Bethea Goodwin, VP of Membership at ITI, uses AI as a research accelerator for keeping pace with global policy developments, but says it requires human validation and should complement existing expertise, not replace it.

Communications belongs at the center of organizational strategy because without clear translation, expertise stays locked inside and fails to reach the audiences that need it.

I’m the go-to liaison between our staff and our members, translating what our experts know into something our members can actually use

The best association communications leaders aren’t broadcasting information. They’re translating it. Inside organizations where policy expertise runs deep and member audiences range from mid-level managers to C-suite executives, the ability to convert technical knowledge into something people can actually use is the skill that matters most.

Natasha Goodwin’s work is a case study in this approach. As the Vice President of Membership at the Information Technology Industry Council, she has built a career on this principle. Recognized for her leadership by Ragan and PR Daily, and with a distinguished background including senior roles at the Association for Psychological Science and the American Nurses Association, Goodwin has honed a specific expertise: turning the dense work of policy experts into compelling narratives that drive member engagement and demonstrate organizational worth.

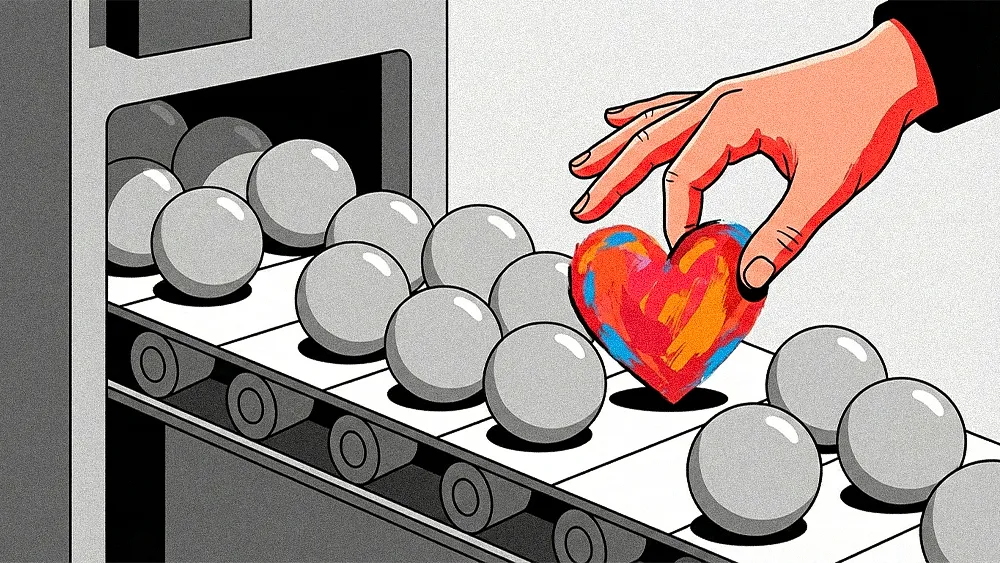

"I’m the go-to liaison between our staff and our members, translating what our experts know into something our members can actually use," says Goodwin. The core of her work is managing two fundamentally different audiences. Policy experts inside the ITI carry deep context and can go granular on any issue at a moment’s notice. Members need something different entirely.

Two audiences, two languages: "With staff, I don’t have to have as much context because they know what’s going on. They can write a whole paper about cybersecurity," Goodwin explains. "But conveying that to members, you have to drill it down. Our members might be sending this to an executive who just wants five bullet points."

Built on relationships: That translation only works when it rests on trust with internal subject-matter experts. Goodwin didn’t come from the tech industry, which made early investment in those connections essential. "Taking time to get to know everyone, figure out what their goals are, and how I can help them made it very easy to communicate to our members. I know what our staff needs and what our members are looking for."

Goodwin describes a feedback loop that most traditional communications structures don’t offer. Unlike consumer-facing campaigns, membership organizations let communicators survey their audiences, gather input through everything from direct conversations to webinars and virtual events, and adjust in real time. "You can have your finger on the pulse because you actually talk to these people," she says. "You actually know what they want."

AI as accelerant, not authority: Goodwin uses AI primarily for research, but draws a clear line. AI assistants still produce widespread factual errors, and building trust around AI-generated content remains an active challenge as communicators adopt these tools. "I never use AI at face value. It complements what I’m already doing," Goodwin says. When something feels off, she turns to colleagues for validation, reinforcing the principle that human judgment must guide AI output.

Agility over reaction: In a policy environment where AI is accelerating how quickly information travels, Goodwin says six years in her role have taught her that the communicator’s job is to stay ahead, not keep up. "I have to be agile. Not reactive, but proactive, thinking two steps ahead of how I should address or talk about an issue." That discipline applies equally to moments of crisis and to everyday member engagement.

Lead with impact: In a media environment where attention spans are shrinking and audiences increasingly expect transparency, Goodwin says communicators need to open with outcomes. "How did this policy help a community? How did deploying AI in an elementary school help teachers be more efficient?" she asks. "Start with impact so we can bring in that interest." It’s a storytelling approach that prioritizes authentic connection over technical detail.

Goodwin’s approach points to a broader recalibration in how associations position their communications function. Rather than treating comms as a support layer that amplifies work already done, she argues it belongs at the foundation. The communicator who understands both the expertise and the audience well enough to bridge the gap is the one who makes the organization’s knowledge travel. "Communications is the foundation of what we do," Goodwin concludes. "Without it, we can’t thrive. We can’t move forward."